Nutrition

Solving infertility issues: Women selling their eggs for quick money?

The thought of a woman to sell her eggs because of financial challenges may seem too easy a way to make money.

The motivation to do this could be stronger because after all, the eggs are “wasted” every month in a woman who has no plans to conceive and so what is the farce about making some cash out of them.

Currently, there are women or couples who are willing to pay substantial sum of money as compensation to women willing to donate their eggs, and the financial reward offered to an egg donor may often be bait many potential donors cannot resist.

This results in their participation in the egg donation process, oblivious of the risks relative to their health and safety, including loss of fertility and sometimes the death of the donor.

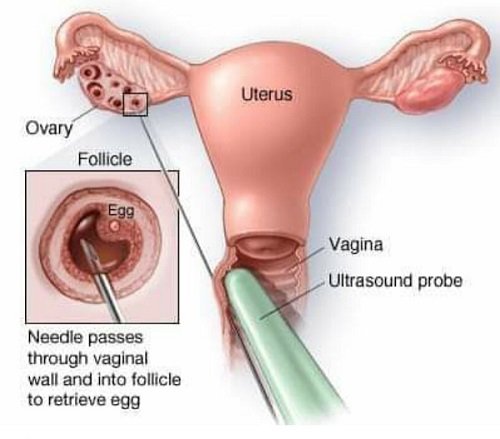

According to a Specialist Obstetrician Gynaecologist with the Women’s Health Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dr Dixie Constantini, in an interview with The Spectator last Friday, said egg donation, medically, was the process by which a woman was given medication to stimulate ovulation and her eggs harvested.

She explained that the choice by a woman to be a recipient of a donor egg generally fell into three categories.

She said that the first were women who were unable to produce viable eggs of their own. The second category included women above the age of 40 opting for assisted reproduction, and the third comprised women who had genetic conditions and wished not to pass on to their children, or who had multiple pregnancy failures which could not be medically explained.

The Obstetrician Gynaecologist said in some cases, the recipient might be a surrogate mother who had offered to carry the baby on behalf of another person or family.

“The recipient could also choose to carry the baby by herself after the donated egg has been fertilised by the semen of her partner. This usually happens when she intends to keep the baby and wants to experience pregnancy on her own” she explained.

She said each month women who had reached puberty and had not gone past menopause released egg from their ovaries, and on rare occasions released two.

“The egg if healthy can be fertilised by an equally healthy sperm. The union of egg and sperm is termed as fertilisation and this is key to any pregnancy occurring. The womb of a woman has a special lining that can increase and decrease in thickness in response to signals received from the body,” DrConstantini said.

She said that while some women donated their eggs purely for monetary benefit, a few others were motivated by altruism.

She said the collected eggs were stored and could be used by other women for the purposes of having a baby by a process known as assisted reproduction.

“Healthy Women between the ages of 18 and 32 are usually considered suitable candidates for egg donation. This criterion is, however, country-specific. A limit to the number of times an individual can donate eggs exists. These limits, set by health authorities of various countries, are intended primarily to safeguard the health of the donor” she said.

She said in some countries the upper limit for donations by an individual was six during their lifetime, however, in other jurisdictions, the upper limit was 10 donations per individual during their lifetime.

DrConstantini cautioned women who wished to donate eggs to be well informed and also go to trusted heath facilities.

“Not all monies are worth it,” she cautioned, as she explained that a person could have fertility problems later in life or even lose her life during egg retrieval if not done well.

She said, it was important that before a person made the decision to become an egg donor, she should know that as much as the process could be complication free, the hormones given before this procedure could have side effects including headaches or bloating.

The Specialist Obstetrician Gynaecologist said the hormones could also come with side effects such as mood changes , extreme enlargement of ovaries, fluid filling the lungs and abdomen of the donor, increased blood clot formation and having a stroke.

She, therefore, advised women to make sure they are thoroughly informed of the risks that come with the procedure,s as they can encounter post procedure and think seriously about the decision to donate egg before they agree to go ahead with signing consent forms to undergo a procedure as such”.

Meanwhile, in an interview with some members of the public in reaction to a question as to whether they would be willing to do an egg donation or be a recipient, there were divergent views.

A student of a public university who spoke on condition of anonymity said she would like to donate her eggs because she was not ready to get married now and felt instead of losing them every month, she would rather give to someone who was desperate.

“I see nothing wrong with it. I feel it is just like donating blood to someone who is in dire need of it. The person will be eternally grateful to you and even bless you. I would like to do it for free than sell it. It would make me feel better “ she said.

“Under this economy I wouldn’t mind selling my eggs. I will make good money and I don’t think this is a crime or sin” a trader also said.

A 40-yea-old nurse said if she had found herself desperate to have a child as a younger person, she would have gladly gone for the option of being a recipient of another person’s egg.

She was, however, concerned that there was not “straight forward “ laws in the country regulating the practice and so might give room to abuse by young girls or women which would and compromise their health.

From DzifaTettehTay, Tema.

Nutrition

The First 1,000 Days: Why Ghana’s investment in maternal and child nutrition matters for human capital development

From the start of pregnancy to a child’s second birthday, the first 1,000 days, represents the most important window for human development. Good nutrition shapes the foundation.

During this short window, the body and brain grow at a pace that will never be repeated. When nutrition is inadequate, the damage to physical growth and cognitive development is often permanent. No later investment in education or healthcare can fully reverse these losses. Ghana’s future workforce and economic progress depend on getting nutrition right during this critical period.

Science is clear. A baby’s brain develops rapidly during pregnancy and early childhood, forming the foundation for all future learning and health. Adequate nutrients during pregnancy support the formation of neural connections that underpin learning, memory, and emotional regulation. When pregnant women lack essential nutrients, their babies begin life at a disadvantage. When young children experience severe malnutrition, they miss critical growth periods that do not return.

Ghana faces serious challenges during this critical window. An estimated 68,517 children suffer from severe acute malnutrition. Between 37 and 63 percent of pregnant women are anemic, with iron deficiency particularly common in late pregnancy. These problems translate directly into diminished potential. Malnourished children perform worse in school, earn less as adults, and face higher risks of chronic diseases. The economic losses multiply across generations.

Research worldwide shows that nutrition investments during the first 1,000 days deliver exceptional returns. Well-nourished children learn better, perform better academically, and become more productive adults. Countries that invest in early nutrition experience faster economic growth through stronger, more productive workforces.

Ghana already has effective solutions. Multiple Micronutrient Supplements for pregnant women reduce the risk of low birth weight and preterm birth, while Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food enables high recovery rates for children with severe acute malnutrition. Both are approved in Ghana’s health guidelines. The problem is not lack of knowledge but lack of access. Coverage remains limited because financing depends heavily on donor support rather than sustainable domestic systems.

Integrating these nutrition interventions into the National Health Insurance Scheme would help close this gap. With a large proportion of mothers and young children already enrolled, NHIS provides a platform for nationwide reach. Recent reforms to health financing further strengthen the case for prioritising essential nutrition services within the scheme.

Ghana’s development agenda emphasizes industrialisation, innovation, and economic transformation. Achieving these goals requires a workforce capable of learning, problem-solving, and sustained productivity. Human capital development, however, does not begin at universities or training centers. It begins before birth.

The first 1,000 days offer no second chances. Each year of delay means another group of children enter adulthood carrying preventable disadvantages. Investing in nutrition during this critical window is not only a health priority; it is a foundational investment in Ghana’s economic future.

Feature article by Womec, Media and Change under its Nourish Ghana: Advocating for Increased Leadership to Combat Malnutrition project

Join our WhatsApp Channel now!

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbBElzjInlqHhl1aTU27

Nutrition

Importance of Fruits During Ramadan

Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic lunar (Hijri) calendar, is a period of fasting, reflection, and spiritual growth. A vital part of observing Ramadan is Iftar—the evening meal with which Muslims break their daily fast at sunset. Fruits play an essential role in Iftar, providing nutrition, hydration, and energy after long hours of fasting.

Here are some of the most recommended fruits to include in your Ramadan meals:

Dates

Dates are traditionally used to break the fast. They are rich in sugar, fibre, potassium, vitamins, and minerals, helping to restore energy quickly after fasting.

Watermelon

Watermelon is highly consumed for hydration, as it is composed mostly of water. It can be enjoyed in slices or blended into refreshing smoothies.

Bananas

Bananas are an excellent source of potassium, which helps maintain fluid balance and reduce thirst. They also provide natural energy to keep you going after fasting.

Apples

Apples are fibre-rich and nutritious, promoting heart health, aiding weight management, and improving digestion.

Cucumber

Cucumber is one of the best hydrating fruits, composed of water and fibre, which aids digestion while revitalising the body.

Pawpaw (Papaya)

Pawpaw is low in calories and sugar, rich in fibre, and promotes healthy digestion, hair, and skin. It is a nutritious addition to any Iftar meal.

Including a variety of these fruits during Ramadan not only helps replenish lost nutrients but also supports overall health, digestion, and hydration throughout the fasting period.

By Linda Abrefi Wadie

Join our WhatsApp Channel now!

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbBElzjInlqHhl1aTU27