Profile

From devastation to glory… Bitter-sweet story of a lawyer who is blind

How would you feel when you woke up early in the morning and realised you were losing your sight – in other words, going blind in both eyes?

This was how it all started for an ambitious young man – Jones Odame, who was dreaming to become an investigative journalist or lawyer.

Dejectedly, on Monday, March 5, 2007, that lofty dream took a devastating blow in the face when Jones, the second-last of eight siblings, woke up with a blurred, grey and dim vision.

Later, the eyes were gone. He could see no more! It was such a torturing experience.

But how did he survive life’s out-of-the-blue turbulence? How did he soar down to the sea and float on it?

Wait a minute. We shall come to that survival story.

Born some 39 years ago to Mr T.G Akyea and Madam Gladys Asantewaa, both of whom hail from Anum – an Akan community in the Asuogyaman District of the Eastern Region, Jones began his basic education at Akwatia – also in the Eastern Region – and continued at the Anum Presbyterian Senior High School from where he proceeded to the Peki Teachers Training College in the Volta Region.

On completion, he taught for two years at Akim Akroso, also in the Eastern Region, until disaster struck one fateful Monday morning.

“I had woken up one Monday morning to prepare for a church programme, as I was the District President of the Young People’s Guild (YPG) in the Nsaba District in the Central Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, when I realised I was going blind,” he recalled.

Immediate reaction: Ceaseless and intense prayers were offered by church members in search of a miracle. Nothing happened.

Tremulous and utterly confused, Jones hurriedly left Akroso on Friday of the same week for the Emmanuel Eye Clinic at East Legon in Accra, which had been recommended to him, in search of solution to the fast-fading sight.

“There, the doctor also directed me to the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital for further assessment after which I was booked for theatre the following Tuesday for a supposed correction of my sight.”

The operation was done. It was retinal detachment repair of the eyes after which he had to spend about a week in the recovery ward.

Finally, the D-day came for the eye shields or bandage to be removed – amid tension and anxiety that had crammed up the ward. His family and friends had come to offer a world of support to him, hoping for the best.

But alas Jones could not regain his sight after the eye-pad had been removed.

“Can you see? Can’t you see anything? Can you see me?” These were words from the eye surgeon that only met a reaction of tears and desolation.

“It was not an easy thing to be told I couldn’t see again for the rest of my life. I was really, really wrecked, heart-broken and devastated,” Jones recollected.

The doctor then advised him to go to the School of the Blind at Akropong in the Eastern Region, since there was “absolutely nothing” that could be done about his situation.

Hardly hit, members of his church at Akroso including one Mr Amponsah, Auntie Mariam from the Netherlands, Kwaku Odame (not his brother) and Reverend Bekai, got some doctors from the USA to confirm that his eyes were truly damaged.

After several failed attempts to restore his sight, Reverend Bekai introduced Jones to a former Head of the School for the Blind, to try to conscientise and introduce him to the Braille. Braille is a form of written language for people who are blind, in which characters are represented by patterns of raised dots that are felt with the fingertips.

“It was there that I realised I had to accept my situation willy-nilly. Indeed, I cried my head off the very first time I touched the braille.”

However, after realising that there was nothing he could do, Jones – as he is affectionately called, begrudgingly agreed to settle for the School of the Blind, where he was first admitted into the Rehabilitation Class.

The Rehab Class is meant for those who were not born blind.

There, he saw a couple of people who had his kind of story including the Counsellor, a Masters Degree holder.

“You can be whatever you want to be in this world through the braille; so don’t be discouraged at all,” were the words of encouragement from the counsellor.

According to Jones, he was hugely motivated by that admonition – and though a year’s course or more, “I spent only two months reading and writing perfect braille.”

With his confidence fully restored and thinking there was no time to waste, he applied and was admitted into the University of Ghana, Legon, to study Political Science and Sociology in 2007.

After four years of diligence, Jones emerged with flying colours – chalking First Class in his area of study.

And, as destiny may have it, he landed at the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) in Accra for his one-year National Service.

“It was there that I realised one of my childhood dreams to be a lawyer was on course.”

So, in 2014, he applied to the University of Ghana School of Law, where he passed an entrance examination to pursue a Bachelor of Laws degree (LLB) – completing in 2016.

Thereafter, Jones gained admission into the Ghana School of Law (Makola), but had to defer the course for two years after the 2016-2017 academic year, owing to reasons he said, were personal.

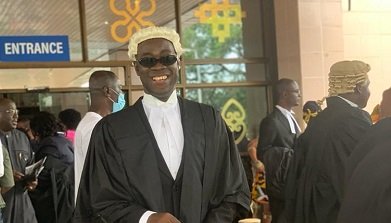

He, however, bounced back ‘gallantly’ in 2020 to complete his course and was called to the Bar on Friday, October 1, 2021.

The day was a historic one for Lawyer Jones Odame as he was given a standing ovation by the Chief Justice (CJ) Kwasi Anin-Yeboah, the former CJ Mrs Georgina Theodora Wood, the Attorney General and Minister of Justice, Mr Godfred Yeboah Dame and an array of eminent justices, when his name boomed from the ‘loud speakers’ as among the 278 lawyers called to the Bar. Apparently, his story was known to all of them. They know it has taken him a Himalayan effort to make the journey.

This year’s event – held at the International Conference Centre in Accra, was the 58th Anniversary in the history of enrolment on the Roll of Lawyers.

“It’s been a hard, tortuous journey, but thank God I have been able to achieve my childhood dreams,” an elated Lawyer Odame, who is married with two children (twins), told The Spectator.

He advised the visually impaired or those who unfortunately find themselves in his situation, not to give up but strive hard to achieve their goal.

“You don’t have to take your life or throw up your hands in despair when confronted with a situation like mine. Life itself is not easy, but with focus and that intrinsic motivation, you can achieve your dreams,” he asserted.

Lawyer Odame took the opportunity to express his appreciation to the Director of the School of Law, Mr Maxwell Opoku Agyemang, the two Registrars of the school and his 2016-2017 Year Group, adding that “this success wouldn’t have come without their encouragement and financial support.”

For now, Lawyer Odame is dreaming of working with the United Nations to champion issues relating to disability.

“Having lived as a sighted person and now as a person who is blind, I have become passionate on issues relating to disability and how they are handled in our society – and will, therefore, wish to work with the UN or any reputable NGO which mandate is to promote the welfare of persons with disability.”

By John Vigah

Profile

Edwina Anokye-Bempah Redefining Trust in Ghana’s Real Estate Landscape

Every morning begins the same way for Edwina Anokye-Bempah, with quiet devotion. It is her grounding ritual, a moment of reflection and gratitude before she steps into the dynamic, often unpredictable world of real estate brokerage.

By the time she arrives at the office, she has already set the tone for her day. She reviews the previous day’s tasks, checks what was accomplished and what still needs attention, and then drafts a new to-do list. For her, success is rooted in deliberate planning, discipline, and the commitment to follow through.

Today, Edwina stands out as one of Ghana’s promising real estate brokers, but she is also clear about the distinctions within her field. While many people casually use the term ‘realtor,’ she is quick to explain that only professionals registered with the National Association of Realtors can claim that title.

“Since I am not registered with the association, I am a real estate broker,” she says. It is a role she embraces wholeheartedly, facilitating transactions, connecting buyers and sellers, and ensuring clarity and integrity at every step.

Her journey into the industry took shape at MeQasa, an online platform dedicated solely to real estate. The platform exposed her to developers, agents, and the complexities of property transactions. She worked closely with developers and observed one recurring problem: clients often complained about agents who failed to respond, follow up, or provide accurate information.

With her background in sales and marketing, Edwina felt naturally drawn to the field. It was an industry where she believed she could make a meaningful, positive impact. Real estate, she came to learn, is far more than brick and mortar. It is about helping people secure one of the most important investments of their lives. This understanding shapes every decision she makes.

One of the most challenging tasks in her work is qualifying clients.

“A serious buyer must be willing, ready and able,” she explains. When one of these three qualities is missing, the transaction is likely to stall or collapse entirely.

On the seller’s side, due diligence is equally critical. Ownership disputes, land fraud, and unclear documentation remain some of the biggest risks in Ghana’s real estate sector.

Edwina understands the weight of the responsibility she carries. “The money involved is huge. These are people’s lifetime savings. Most people buy one home or maybe two in their entire lives. You cannot afford to make a mistake.”

Working in what many describe as a male-dominated field has never intimidated her. With an MBA in Marketing and extensive experience in sales roles including a stint as an Account Manager in an advertising agency, she has grown comfortable handling clients, negotiating deals, and presenting herself with confidence.

“My gender has never discouraged me,” she says. “What matters is hard work and ensuring that the client’s needs were met.”

The only occasional challenge, she admits, was maintaining professional boundaries when some men attempt to be overly familiar. Her solution is simple: stay professional and do not over-familiarise yourself with clients.

Her educational journey started in Kumasi, followed by Yaa Asantewaa Girls’ Senior High School, where she studied Agricultural Science. She continued the same at the University of Ghana before pursuing her master’s degree. After university, she worked on her uncle’s poultry farm before moving into advertising. Later, her role at MeQasa finally opened the door to the career she had long been unknowingly preparing for.

Over the years, Edwina has built a reputation not only for competence but also for care. She recalls one client in particular, an older man relocating to Ghana with no family in the country. After helping him secure two homes, she became the closest person he could rely on. One evening at around 8 p.m., he called to say he felt unwell. Without hesitation, she drove to his home and rushed him to the hospital. Doctors later told her that any delay could have been fatal.

For Edwina, that moment affirmed that the job goes far beyond selling property. “It doesn’t end with the sale,” she says. “You have to look out for people.”

Her influence also extends to younger people observing her journey. She is known for her tenacity, her refusal to give up on clients or tasks, and her resilience in the face of challenges. Those who work around her learn to push forward regardless of setbacks.

“If a deal doesn’t go as expected, you don’t look back. You find a way.”

Beyond real estate, Edwina serves as an interpreter in her church, a role that dramatically boosted her confidence. What began with trembling legs has evolved into a boldness that reflects in her public speaking and client interactions. She credits her growth to God, her senior pastor, her mother, siblings, friends, and her dedicated team — “an amazing circle,” she calls them.

Today, she is also a partner in a showroom business dealing in vanity units, sanitary wares, and tiles, an extension of her real estate insight and experience.

For young people aspiring to join the industry, her advice is clear: “Learn the industry beyond selling. Understand transactions, build strong relationships, and always do your due diligence.”

For Edwina Anokye-Bempah, real estate is more than business; it is trust, service, and impact, one client at a time.

By Esinam Jemima Kuatsinu

Join our WhatsApp Channel now!

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbBElzjInlqHhl1aTU27

Profile

How a Collapsed Dream Birthed Another: Daniel Debrah’s Music Journey

From the age of five, Daniel Nana Kwesi Kakra Debrah has lived a life surrounded by rhythm, harmony, and the quiet pulse of music. Growing up in a home where instruments filled corners and rehearsals were as normal as conversation, Daniel’s first teachers were not in formal classrooms—they were the sounds, movements, and discipline he absorbed from his father, a committed church musician.

Ironically, music was not Daniel’s first dream. Like many young boys, he once hoped to become a professional footballer. But an injury from a school match left him unable to walk for three months, forcing him to retire that ambition. What seemed like a tragedy at the time became the turning point that aligned him with the path he was always meant to follow.

Daniel’s earliest musical expression began in church. As a boy in Sunday School, he eagerly ‘pounded’ the drums, quickly becoming known as the child who never missed an opportunity to play. Even in Senior High School (SHS), although many of his classmates were unaware of his talent, he continued practising quietly until completing school in 2005.

After SHS, Daniel joined a church music class with the intention of growing as a drummer, but one moment changed everything. Watching a bass guitarist perform stirred something in him. Drawn to the deep, steady tones of the bass, he persuaded a friend to teach him the basics. With no instrument of his own, Daniel practised at home using a broken guitar for more than eight months.

Then destiny intervened. The church’s lead bassist was suddenly suspended, and Daniel stepped in voluntarily during an evening service. That temporary voluntary act became permanent as he was asked by the then Music Director to fill in the gap. From that point, he embraced the bass guitar fully—a decision that defined the rest of his life.

Around 2006, Daniel made a life-changing decision to take his craft seriously. He began practising for hours on end, sometimes up to eight hours a day, often without food, locked away from family and friends, perfecting techniques and expanding his creativity. While others assumed he was outdoors socialising, Daniel was indoors sharpening his gift.

His breakthrough came in 2007 when he performed in the TV3 Bands Alive competition. The exposure, applause, and feedback confirmed his dream: “music was not just a passion; it was his calling,” he said.

With time, Daniel moved confidently into the professional space. He performed at studio sessions, live concerts, weddings, church events, and high-profile national programmes. His talent, discipline, and reliability earned him a reputation that continues to attract respected gospel artistes.

Today, he works closely with Daughters of Glorious Jesus, Chris Apau, and Israel Ofori, who have been of immense help to his career ministry. He also collaborates with several ministries and offers support with musical arrangements, live performances, and studio recordings.

Beyond the stage, Daniel sees himself as a mentor. Many young musicians reach out to him, some visiting in person, others calling for guidance. Whether through hands-on training or virtual coaching, he is always ready to teach. For Daniel, music is not just technique; it is character, discipline, and values. He believes a musician must carry integrity both on and off stage.

Like many musicians in Ghana, Daniel has faced challenges with delayed payments and broken agreements. These experiences have taught him to value professionalism. He now insists on part payment upfront and charges more for his services, a decision grounded in self-respect and fairness.

Daniel’s journey in music has been shaped by various individuals who have supported him at different stages of his career. He acknowledged Opoku Agyeman Sanaa, Kofi Ennin, Andrew Klu, Mr. Samuel Abbey, Mr. Samuel Sarpong Agyei, Paul Quartey, Mr. Nene Emmanuel, and Mr. Isaac Asiedu, saying that their belief in him continues to inspire his journey.

Daniel’s work is guided by his Christian faith. He sees music as ministry, not merely entertainment. Off stage, he is a devoted family man—a husband and father of two, a boy and a girl, who have also started playing musical instruments. During his leisure time, he listens to music, or plays football and action video games.

Through his acts of service and unwavering determination, Daniel continues to inspire others, proving that when passion meets integrity, ordinary men impact the lives of others.

By Esinam Jemima Kuatsinu